18/02/2021

Post Link13/02/2021

Post LinkWinnowing MMXXI

Canada pushes abundant PhD graduates towards industry needs | Times Higher Education (THE)

Canada’s universities need to adjust their doctoral degree programmes to help make their swelling surplus of PhD graduates more attractive to industry, a government-chartered assessment has concluded.

Perhaps they need fewer PhDs. And as for how to make a bad situation worse:

Universities, meanwhile, should keep adjusting the content of their doctoral degree programmes to include skills in management, teamwork and communication that are valued by companies, the experts say.

David Hubel, a Canadian by birth, and a Nobel Laureate, wrote that one of the advantages of having an MD was that — in those days, but not now — you didn’t need to do a PhD. Like many so many of his ideas about doing science, he was spot-on. I was delighted to have got through in the wonderful bad-old days, managing to avoid this credential.

Its just business

Australian universities in ‘deep trouble’ as borders stay closed | Times Higher Education (THE)

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, said in 2018 that Australia was poised to overtake the UK as the second most popular global destination for international students in 2019. However, speaking to Times Higher Education, he said it was now “impossible to see that position being restored.…in fact, Australia may not recover market share in the longer run”.

He goes on:

My sense is that international education in Australia is in deep, deep trouble. That means higher education is in deep trouble and scientific research is in equally deep trouble because this is heavily financed from international student fees.

One commentator on this report states:

Australian Universities are at a cross-roads and along with them the huge international education market (our 3rd biggest export industry), yet our politicians are doing nothing… It is unimaginable that any other large export industry would be so conscientiously ignored. [emphasis added].

Rich DeMillo describes higher education as a multisided marketplace. It is a feature of our age that cross-subsidies within such marketplaces will come under strain. If you want to do research, you need to fund it; if you want high-quality teaching, you have to fund it on its merit. No free lunch.

Precisely what?

Precision medicine in rheumatology: are we getting closer? — The Lancet

One of the things that led me to become disenchanted with much of modern medical genetics was the hype that was necessary to secure funding. Genetics is a great way to do biology, but biology is not synonymous with medicine; advance in one does not necessarily follow from the other.

And personally speaking, the best reason for the study of modern human genetics was to tell the story of humanity — how we got here, and what is our story. It is sad that there is no Nobel for biology.

Precision medicine is another (IMHO) bullshit phrase. Read this recent Lancet article (link above):

The overarching aim of precision (also referred to as personalised) medicine is to identify the best possible management approach for an individual with a certain disease. The main prerequisite for such an approach is the identification of characteristics linked to a favourable outcome of a certain treatment. The characteristics of interests might be clinical or molecular biomarkers or identified through imaging, allowing for stratification of patients and prediction of response. The size of the strata might range from big subgroups covering a substantial proportion of patients to individual patients.

But medicine has always worked this way. You don’t give children the same dose of drugs as adults; you don’t treat all cases of psoriasis the same way. And as for biomarkers, well, over a century ago there was the H&E project (H&E standing for the two most common dyes used in diagnostic histopathology), a discovery that still predicts outcomes better than all those wonderful machines in the Sanger centre (and they are wonderful).

And then in Science I read:

A genome to celebrate | Science

The completion of the draft sequence laid the foundation for a new precision medicine paradigm that aims to use a person’s unique genetic profile to guide decisions about the treatment and prevention of disease. We have already seen some signs that precision medicine is possible, and although off to a slow start, the promise of this approach may ultimately be realized.…. Given the pace at which breakthroughs based on the human genome sequence are happening, when we next commemorate the publication of the draft human genome sequence, be it at 25, 30, or 50 years, we may look back again, realize that this accomplishment was a watershed for the biological sciences, and marvel at how far we have come in such a short period of time. [emphasis added].

We might indeed, but the phrasing reminds me of the celebrations that used to surround a grant being awarded, rather a discovery made. I, too, should confess on this point.

Please, oh please, a little modesty and perspective. We are not in sales.

That Welshman

Here is something more solid and sustaining; something where the purpose of language is to communicate and not to shill.

I have been reading Nye Bevan’s biography by Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds. Here is an excerpt from a speech Bevan made in 1959.

I have enough faith in my fellow creatures in Great Britain to believe that when they have got over the delirium of the television, when they realize that their new homes that they have been put into are mortgaged to the hilt, when they realize that the moneylender has been elevated to the highest position in the land, when they realize that the refinements for which they should look are not there, that it is a vulgar society of which no person could be proud, when they realize all those things, when the years go by and they see the challenge of modern society not being met by the Tories who can consolidate their political powers only on the basis of national mediocrity, who are unable to exploit the resources of their scientists because they are prevented by the greed of their capitalism from doing so, when they realize that the flower of our youth goes abroad today because they are not being given opportunities of using their skill and their knowledge properly at home, when they realize that all the tides of history are flowing in our direction, that we are not beaten, that we represent the future: then, when we say it and mean it, then we shall lead our people to where they deserve to be led.

12/02/2021

Post LinkWinnowing XXMMI

More evidence in the case against Luxembourg | Financial Times

Luxembourg sometimes resembles a criminal enterprise with a country attached.

Via The Tax Justice Network and Cory Doctorow

666 trademarks and all that

Mark of the Devil: The University as Brand Bully by James Boyle, Jennifer Jenkins :: SSRN

James Boyle is a Scottish law professor at Duke. He is one of the leading academics in the field of IPR. His book Shamans, Software and Spleens: Law and Construction of the Information Society opened my eyes to a world that I literally did not know existed. It is hard to live a game when you fail to understand not just the nature of the rules, but the idea that there are rules. I would also plug his graphic book on IPR and music Theft: A History of Music.

He has now obviously been studying things closer to his own academic home.

In recent years, universities have been accused in news stories of becoming “trademark bullies,” entities that use their trademarks to harass and intimidate beyond what the law can reasonably be interpreted to allow. Universities have also intensified efforts to gain expansive new marks. The Ohio State University’s attempt to trademark the word “the” is probably the most notorious.

I don’t have a reference, but one of the delivery companies (DHL, Fed Express etc.) tried to get IPR — wait for it — not for their package design but over the dimensions of air that the package encompassed.

On being human

Academic jailed in Iran pulls off daring escape back to Britain | Iran | The Guardian

“They started on me in a very, very small room, it’s almost like a grave. You have three army blankets, one as a cover, one to sleep on and one as a pillow. For 24 hours there is a bright shining light on top of your head, a Qur’an, a mohr on which Shias pray, and a phone to contact the guards to take you to the toilet. There is no natural light, and a window in the prison door opens through which they put your food. That is your only communication with the outside world. It is incredibly quiet, and you just become crazy. You don’t know what time it is, and you don’t know what will happen next.

“When you are taken out to go to the toilet, or half an hour’s fresh air or to be interrogated you are blindfolded. And then your interrogation becomes your lifeline, it’s so sad that you want to be interrogated more because that is the only way you can communicate with a fellow human being. [emphasis added]

The Irish pol is a revenant from a dead era.

Can Joe Biden make America great again? | Books | The Guardian

Probably not…but some nice words (again from Fintan O’Toole)

In normal times, this rhetoric would seem ludicrously over the top, all the more so coming from a garrulous, glad-handing old Irish pol, who spent 36 years in the Senate and eight as vice-president. Biden is not obvious casting for the role of apocalyptic warrior.

The impulse comes with the territory of Biden’s Irish Catholicism, its fatalistic view of this earthly existence as, in the words of the rosary, a “valley of tears”. This is, as Biden sees it, “the Irishness of life”.

Biden the Irish pol is a revenant from a dead era. His skills as an operator, a fixer, a problem-solver, are finely honed — but they are redundant. He is a horse whisperer who has to deal with mad dogs. He is a nifty tango dancer with no possible partners. There is no reasonable, civilised Republican opposition with which he can compromise. There can be no such thing as a unilateral declaration of amity and concord.

The great problem of American political discourse has always been — strangely for such a Biblical culture — a refusal to accept the idea of original sin.

Surprise, surprise

No confidence vote in Leicester v-c as 145 at risk of redundancy | Times Higher Education (THE)

Union members at the University of Leicester have voted in favour of a motion of no confidence in the vice-chancellor in response to the threat of redundancies across the university.

A Leicester spokeswoman said the university was “naturally disappointed to learn about [the] vote of no confidence”.

10/02/2021

Post Link07/02/2021

Post LinkWinnowing MMXX1

Britain Alone: the Path from Suez to Brexit, by Philip Stephens

I know little about Paul A Myers except that he is one of the sharpest commentators on the online FT comments forum.

Britain made a bad choice with Brexit. The coming years will probably reveal just how much. It failed the one test it had to make as an international strategist in the opening decades of the 21st century. It is inevitably going to wind up with something smaller and less influential — and probably less prosperous. But then it has been making bad choices for a long, long time.

When London is able to imagine itself as a bigger and similarly successful Copenhagen, then new geopolitical success will await. Apparently just some such thinking is taking hold in Edinburgh.

As for Edinburgh, I truly wish that to be the case.

The Capitalist Case for Overhauling Twitter

This next quote is via Scott Galloway in the New York Magazine.

The political philosopher Hannah Arendt, analyzing the fall of democratic Germany to the Nazis, observed that totalitarianism comes to power through a “temporary alliance between the elite and the mob.”

The following is from John Naughton, one-time TV critic of the Listener, and who effectively introduced me to the world of blogs and tech a long, long, time ago.

A few years ago, during a period when there was much heated anxiety about “superintelligence” and the prospects for humanity in a world dominated by machines, the political theorist David Runciman gently pointed out that we have been living under superintelligent AIs for a couple of centuries. They’re called corporations: sociopathic, socio-technical machines that remorselessly try to achieve whatever purpose has been set for them, which in our day is to “maximise shareholder value”. Or, as Milton Friedman succinctly put it: “The only corporate social responsibility a company has is to maximise its profits.”

Desmond Morris in one of his popular ethology books pointed out the logical flaw in the arguments that posits that war is a function of individual violence, whether the origins of the latter are inherited or acquired. The propensity to cooperation over dissent is problematic.

The following is from a review of The Goodness Paradox by Richard Wrangham. The subtitle is: How Evolution Made Us More and Less Violent.

Homo sapiens see-saws endlessly between tolerance and aggression. To parse our paradoxical nature, primatologist Richard Wrangham marshals gripping research in genetics, neuroscience, history and beyond. His lucid, measured study ranges over types of aggression, the evolution of moral values, the age-old problem of tyrants, and war’s “coalitional impunity”. The propensity for proactive violence, he argues — forged by self-domestication, language and genetic selection — marks out our primarily peaceful species. We uniquely bend cooperation to ends both cruel and compassionate. [emphasis added].

05/02/2021

Post LinkThat was then and this is now

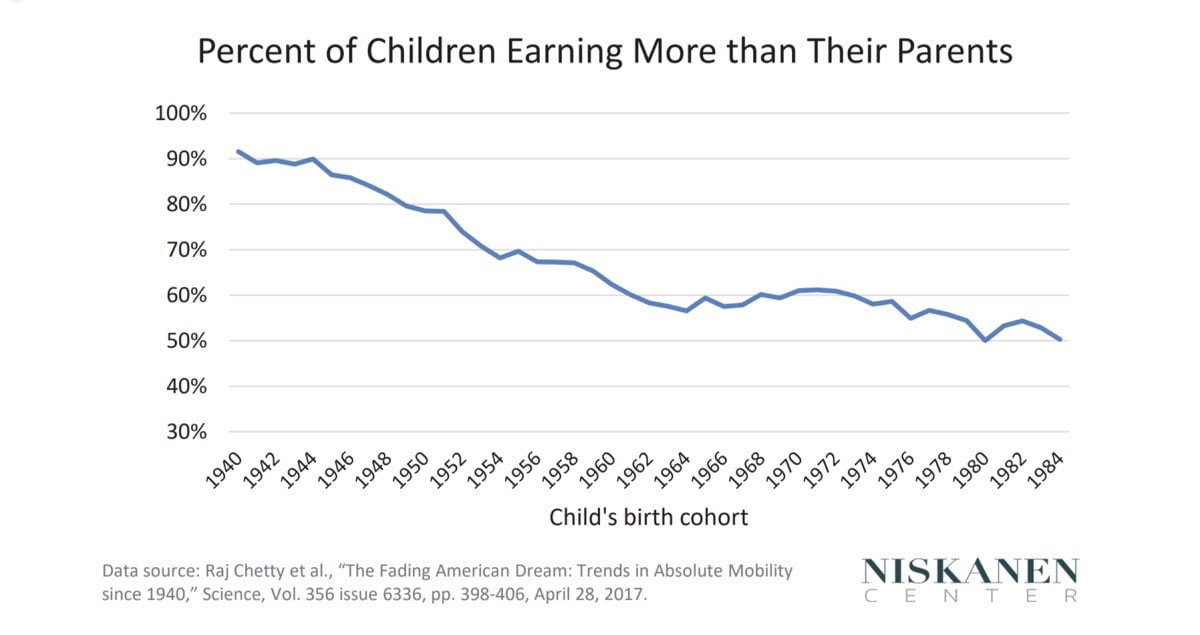

This is a slide from a John Kay talk. It is a few years old but the message resonates more than ever.

05/02/2021

Post LinkLife on the margins

Life on the margins

There are two gangs of people you tend to see loitering in or close to hospitals. Groups of smokers (staff or patients) trying to find a safe-space close to, but outwith, the official perimeter. And medical students, forlornly waiting for the teacher to arrive.

04/02/2021

Post LinkWriters start early:

Richard Flanagan: ‘Art was something that happened elsewhere’ | Financial Times

No, this is not the advice about getting 500 words in by sunrise, but rather a fun Lunch with the FT column.

FT: By the time I sit down with Richard Flanagan, he is armed with a glass of champagne. Technically speaking, it is a sparkling white wine from a vineyard in Tasmania, the remote Australian island state that the Booker Prize-winning novelist has lived in for all but three and a bit years of his life. Everyone calls it champagne in Australia but either way, Flanagan is not just drinking it but knocking back hefty swigs of the stuff.

“I’ve also got an Armagnac, just to help me along,” he says.

FT: I laugh uncertainly. Each to his own and all that, but it is barely 7 o’clock in the morning in Hobart and I had been expecting to see him with at least a slice of toast.

Whether it is the booze or not, Oxford doesn’t come out of it too well.

“Well,” he says, staring into the distance for so long that I think my screen must have frozen. “What can I say?” he eventually says, 28 long seconds later. “I found it a place of sublime emptiness.”

FT: He was, he says, surrounded by people from whom he felt utterly alienated. One don told him Australia had no culture. Another routinely addressed him as “Convict”. The whole place left him cold.

“These were people who thought women were slime. These were people who thought black people were apes. These were people who didn’t think they were the master race, they knew it.” Another pause. “I went from a universe of wonder to a storied place and I discovered to my astonishment it was small,” he says. “Oxford above all else is a bit dull.”

On his books not been viewed favourably closer to home, in Australia, and his decision to not enter them for the Miles Franklin Award, one of Australia’s oldest and most important literary prizes.

“I just decided I wouldn’t enter it any more,” he says quietly. “Prizes need writers but writers don’t need prizes.” [emphasis added]

03/02/2021

Post LinkWhat’s in a name?

Metabolic surgery versus conventional therapy in type 2 diabetes – The Lancet

I like the parlour game of inventing collective nouns for doctors — a ganglion of neurologists, a scab of dermatologists, and so on— and I also cannot help but smile when Mr Butcher turns out to be, well, a surgeon, and Lord Brain is a…. You get it.

I saw this article when I was skimming through the Lancet the other week, and something tweaked in my mind from long-back.

Metabolic surgery versus conventional therapy in type 2 diabetes. Alexander D Miras & Carel W le Roux

A few more details:… “report their trial in which they randomly assigned patients to metabolic surgery or medical therapy for type 2 diabetes.1 60 white European patients (32 [53%] women) were evaluated 10 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), biliopancreatic diversion (BPD), or conventional medical therapy.

Now, I suspect the name Roux is not rare but of course checking with Wikipedia, I can remind you:

César Roux (23 March 1857, in Mont-la-Ville – 21 December 1934, in Lausanne) was a Swiss surgeon, who described the Roux-en-Y procedure.

No relation to Ross-on-Wye.

01/02/2021

Post LinkTo err is human

In the middle of the pandemic, I got an e-mail asking whether I had access to data from the experiments behind a paper I’d published in 2014. Three months later, I requested that the paper be retracted. The experience has not left me bitter: if anything, it brought me back to my original motivation for doing research.

This is a disarmingly honest piece (in the journal Nature) about how mistakes in the analysis of complicated data sets caused inappropriate conclusions, leading, in this case, to a retraction of a manuscript.

As a student, I was even told never to attempt to replicate before I publish. That is not a career I would want — luckily, my PhD adviser taught me the opposite.

John Ziman warned over 20 years ago in Real Science that we were entering post-academic science. Here are some words of his from an article in Nature.

What is more, science is no longer what it was when [Robert] Merton first wrote about it. The bureaucratic engine of policy is shattering the traditional normative frame. Big science has become a novel way of life, with its own conventions and practices. What price now those noble norms? Tied without tenure into a system of projects and proposals, budgets and assessments, how open, how disinterested, how self-critical, how riskily original can one afford to be?

As the economists are fond of saying: institutions matter. As do incentives. Precious metals can be corrupted, and money — in the short term — made.